Four years of ILL service at the Faculty Library of Arts and Philosophy (Ghent University): Findings and challenges

Joris Baeyens

Abstract

This paper aims to give an insight into the working of ILL services at the Faculty Library of Arts and Philosophy of the Ghent University. Additionally, we take a closer look at two challenges in the field of ILL: e-book lending and controlled digital lending (CDL). Putting these challenges into practice can give a new incentive to ILL. At this moment, however, it’s still work in progress.

Keywords

Interlibrary loan; ILL; E-book lending; Controlled digital lending; CDL; Digital rights management; DRM; Licences; Copyright

Article

Introduction

In June 2018 the Faculty Library of Arts and Philosophy (Ghent University) started its own ILL services. Previously ILL requests were handled by Ghent University’s central library (also known as the Book Tower).

During this four-year period we have gained an insight in the world of ILL. This paper is about these insights, but also about the challenges ILL faces more broadly.

These challenges mainly concern the transformation of print ILL into digital ILL. At the present moment, ILL staff still have to deal frequently with processing print books, the so called ‘returnables’. This may change from the moment a legal framework is put into practice for the cases outlined below:

- making e-book licences lendable for ILL;

- making a digital copy of a print book lendable through CDL.

Both these challenges will be explored further on.

This paper is derived from the presentation I gave at the European Staff Week in Liège, June 2022.[1] The enriching presentations and discussions with colleagues gave extra input to this paper.

ILL platforms as primary vehicles

When started in 2018 our ILL Service had access to four ILL platforms (or providers): Impala (Belgium), Subito and Gateway Bayern (Germany) and Sudoc (France). Later on, we joined OCLC WorldShare ILL (June 2019) and RapidILL (May 2020). It was clear from the beginning that these platforms are essential vehicles for ILL work. To underline this: in 2021, 96% of all ILL requests were processed via ILL platforms. As a consequence, sending an email directly to libraries to obtain an ILL has rather become an act of last resort (Posner, 2019).

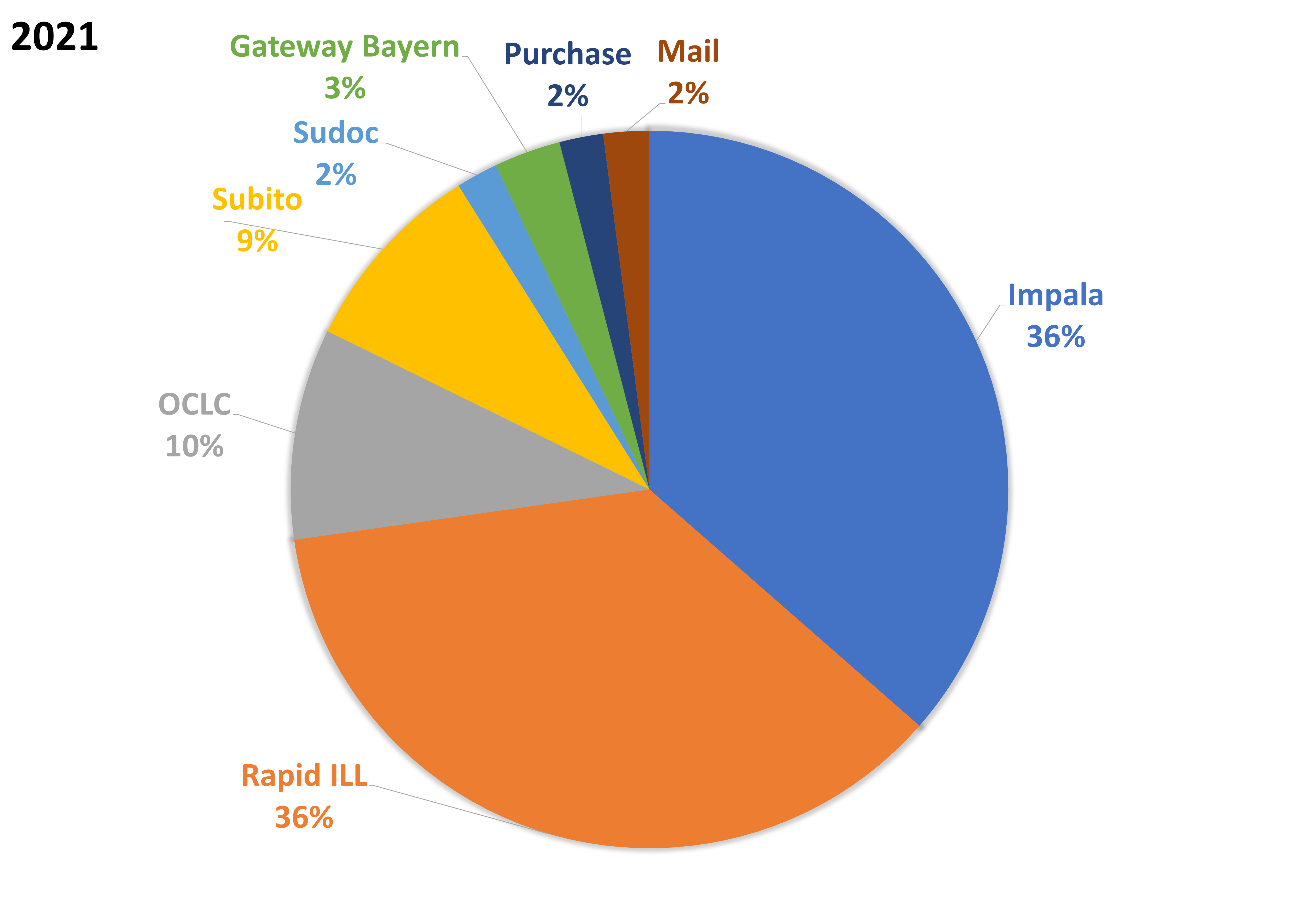

Figure 1 shows the fulfilment rate of ILL requests in 2021 per provider. The two main providers, Impala and RapidILL, are explained in more detail below.

Having access to a range of providers significantly increases the chances of a positive ILL outcome. Which provider to choose first is often made on the basis of a WorldCat search as this gives a good indication of which libraries hold the item. Besides availability of the item, other criteria are also taken into account, such as rate, sending costs, import duties, loan period. Overall, one can say that an assessment of the above elements determine which provider and consequently which library or series of libraries are addressed.

Impala

Impala—developed by Antwerp University—is Belgium’s national ILL provider since 1992. It has a large pool of members ranging from Belgian university libraries to public and subject libraries. In 2021, Impala represented 36% of our ILL transactions, mainly for print books. Twice a week a car shuttle transports ILL requested print books to and from Belgian universities. Being centrally located, the campus of Vrije Universiteit Brussel serves as exchange hub. Given that Belgium is a small country this shuttle system has proven to be cost-effective and efficient. Therefore Impala is our first choice for print material.

RapidILL

In terms of ILL requests, RapidILL is on a par with Impala: both represented an equal share of 36% of ILL requests in 2021. Thanks to its high fulfillment rate and short delivery time RapidILL has ‘rapidly’ become our premium provider of non-returnables (articles and book chapters).

The foundations of this platform were developed by ILL staff at Colorado State University Libraries in 2001, then taken over in 2019 by Ex Libris/ProQuest (Ex Libris, 2019) that further expanded and commercialized the platform.

To unravel the success of Rapid ILL it may be interesting to have a closer look at its main characteristics (Ex Libris, n.d.):

- Related libraries are organized around ‘pods’. These pods are created to support peer or consortium resource sharing. A library can take part in several pods. A group of libraries can ask ProQuest to create a new Pod (California Digital Library, 2022).

- The use of algorithms that utilize load-leveling and time zone awareness.

- A holdings database tailored to resource sharing needs. The database matches requests down to the year level. Holdings are updated on a six-month cycle.

- A library’s local holdings are checked in terms of availability prior to sending the ILL request.

- Built around a community of reciprocal users.

Recent initiatives

The “HERMES Project” is a library driven initiative, a European project connected with the interlibrary loan and document delivery services, that came into existence during the COVID period (Lomba et al., 2023):

The whole objective of HERMES Project is to support effective access to knowledge for the academic community. To achieve this, HERMES plans to strengthen skills in searching and getting quality academic texts. In addition, and to provide easier access to scientific literature, librarians are the other target of HERMES’ objective: the improvement of librarians’ competencies in terms of resource sharing (RS), and the creation of a more effective international system to share electronic resources.

Early in 2022 the ‘International ILL Toolkit’ was set up by librarians Brian Miller (Ohio State University Libraries) and Lapis Cohen (University of Pennsylvania) in partnership with OCLC. It’s a freely available crowd-sourced database, easily accessible on a Google spreadsheet. The core of the toolkit is a listing of lenders from around the world with contact, delivery, and payment information. It also provides valuable tips & tricks and ILL request templates in different languages (OCLC SHARES, n.d.).

These two initiatives can be applauded for their efforts to make resource sharing freely accessible for all libraries worldwide, especially as membership with most platforms tends to come with a high price tag.

Another new service came from German provider Subito. After 15 years in existence, it has expanded its ILL service to include the delivery of scanned book chapters.

Purchase is considered when ILL is not possible or too expensive. In these cases a short assessment is carried out before switching to purchase. Most often priority is given to students as they cannot rely on funds to order books with our acquisition service. Also publications on subjects that do not fit into our collection are prone to be purchased. ILL requests for recent publications that are not yet available for ILL are redirected to our acquisitions department.

A specific category are (unpublished) PhD theses. Making theses available in ‘open access’ repositories is a fairly recent trend. And older dissertations are still often excluded from ILL, either by the defender’s copyright choice or by a ‘no loan’ policy of the issuing university. Over the years ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database (PQDT) has built a vast collection of PhD theses. When a dissertation cannot be obtained through ILL but is available at PQDT a purchase from this provider is made.

Print versus digital

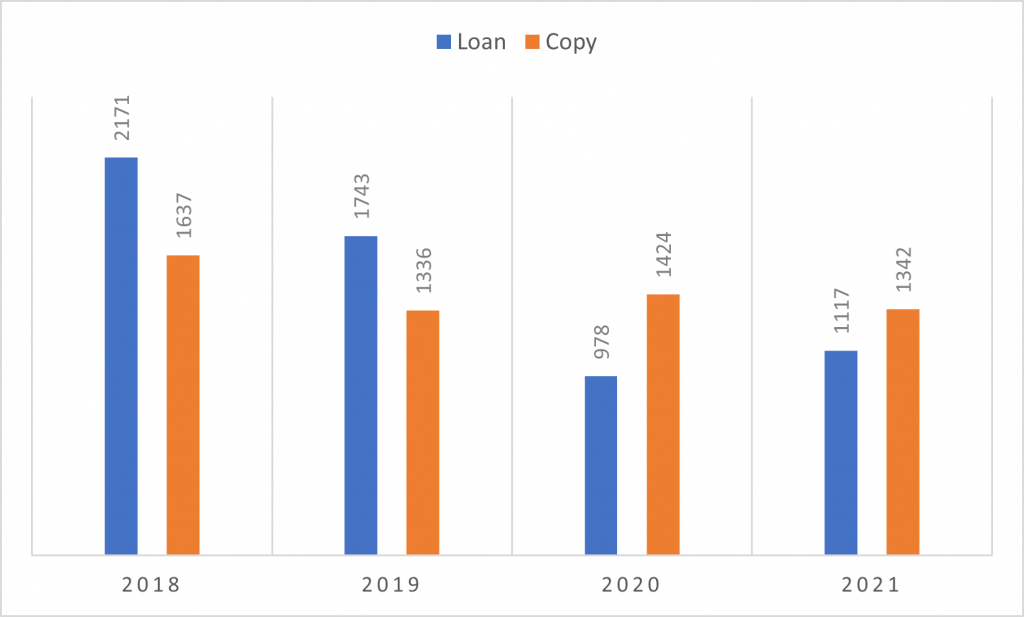

An interesting trend that occurred during 2018–2021 was a shift from ‘print’ to ‘digital’ document delivery at our faculty library. By ‘print’ we mean traditional paper books whereas ‘digital’ refers to either an article or a chapter delivered electronically.

This shift from print to digital occurred in the midst of the COVID period (2019–2020) and continued in 2021 (Figure 2). This evolution towards (more) digital document delivery was undoubtedly accelerated by the physical library closure during the pandemic. Figures for 2022 indicate that this trend more or less persists: we processed 1,019 print requests versus 1,040 digital requests.

Challenges

E-books and ILL

Libraries are evolving towards hybrid providers offering both a paper and digital collection. Within our library, e-book purchase represented 10% of overall acquisition in 2022. In the meantime, several initiatives were taken to increase e-book acquisition such as a financed digital-first collection policy and five EBA’s with major publishers, while two DDA’s have been launched since the beginning of 2023.

A well-known concern amongst librarians is the issue of e-books not being eligible for ILL. This concern is fully legitimate: as libraries’ e-book collections grow less material will become shareable through ILL.

That being said, our ILL service has not yet had to deal with ‘unfulfilled’ requests as a result of “e-book only” availability. To date, there has always been a library that had a print copy for loan.

But it goes without saying that ILL e-book lending would be a big step forward. Several initiatives have already been made to address this issue. Occam’s Reader (USA), a university driven initiative is one of them. With a technical infrastructure fully in place it proves that ILL e-book lending can be successful. The scale of this project is however limited to a number of affiliated research libraries (Greater Western Library Alliance) and one publisher: Springer (OCCAM’S READER, 2021).

A project aiming at a wider scale is ProQuest’s “Whole e-book ILL pilot” (Roll et al., 2022). It was launched in November 2021, with expected outcomes by the end of 2022. This project involves six major publishers and four libraries. The key concept behind this project is making e-book licences lendable between libraries. In a nutshell: when circulating an e-book through ILL, the lending library loses one licensed access during the E-ILL period. The patron of the borrowing library receives an E-ILL URL and has access to the e-book for two weeks via the ProQuest E-book Central platform. The borrowing patron can then make use of the e-book in accordance with the DRM restrictions of the e-book licence. These DRM restrictions can however put a damper on the patron’s user experience. Fortunately, the industry shift towards DRM-free e-books has accelerated in recent years (Rodriguez, 2021, p. 17), which gives libraries the possibility to build a DRM-free e-book collection.

The lack of “lendability” of e-books is the most common issue that has recently been put forward (Weston, 2015, p. 53). If this pilot turns out to be successful and scalable to a wide range of university libraries, it might turn out to be a breakthrough for e-book ILL.

Print books and CDL

As mentioned earlier, print ILL is gradually losing ground to digital ILL. In 2021 however, 45% of our patrons’ ILL requests were still for print books. Almost half of these print book requests were fulfilled through the Belgian ILL Impala network and the other 55% of print books came from abroad.

There are however some significant downsides relating to print book ILL, such as:

- risk of loss or damage during sending,

- cumbersome import formalities for non-EU parcels,

- sending costs and import duties,

- delivery time,

- ecological foot print,

- antiquarian books: too precious for sending.

Another interesting finding is that in 2021 46% of our print ILL requests were for books published before 2000. Apart from some exceptions, it is unlikely that pre-2000 publications will ever appear as an e-book. This is where CDL or Controlled Digital Lending can offer a durable, cost-effective and efficient alternative. Controlled Digital Lending is a model by which libraries digitize their print materials with purpose of making the digital version available for lending.

Controlled Digital Lending has three important requirements (SPARC, n.d.):

- A library must own a legal copy of the physical book.

- A library must maintain an “owned to loaned” ratio: simultaneously lending no more copies than it legally owns.

- A library must take technical measures to ensure that the digital file cannot be copied or redistributed (= implementation of DRM).

Many libraries applied CDL on a local scale during the pandemic and the resulting closure of libraries. They achieved this by making their print materials available in digital format on the basis of user requests. On a broader scale, CDL can be a mechanism for ILL, and certainly one that can be a solution to offset the downsides outlined above.

US and Canadian libraries as well as organizations such as ProQuest and OCLC are already anticipating on the use of CDL as a modern method of ILL. There is however a legal issue preventing CDL from being widely implemented. At the time of writing the Internet Archive, a pioneer in CDL, is involved in a lawsuit with four major publishers on the use of CDL.

This lawsuit and the long-lasting international debate on copyright explain why enabling Controlled Digital Lending is a long-term process. Let’s hope for a positive outcome in favor of CDL. An outcome that gives legal ground to CDL could surely act as a catalyst for wider implementation (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, 2021).

Concluding thought

Referring to a statement by the organizers of this staff week: “No library can buy or hold everything its users need. At a certain point, librarians need to pool their resources and collaborate to provide access to what they don’t have.” The presentations held during the staff week at University of Liège demonstrated the interesting initiatives taken by libraries on how to deal with this challenge in various ways.

The challenges that are dealt with in this paper concern two domains: “e-book ILL” and “ILL-CDL”. Both these domains involve legal and technical requirements that need to be met. The continuing efforts made by libraries, library associations, advocacy organizations and aggregators are smoothing the way. Once these requirements are successfully fulfilled, these domains may, in my humble opinion, well become foundations of a future Interlibrary Loan/Resource Sharing landscape.

Bibliography

Baldwin, P. (2014). The copyright wars: Three centuries of Trans-Atlantic battle. Princeton University Press.

California Digital Library. (2022, April 18). Announcing the WEST RapidILL pod. https://cdlib.org/cdlinfo/2022/04/18/announcing-the-west-rapidill-pod/

Ex Libris. (2019, June 20). Ex Libris acquires RapidILL, provider of leading resource-sharing solutions. https://exlibrisgroup.com/press-release/ex-libris-acquires-rapidill-provider-of-leading-resource-sharing-solutions/

Ex Libris. (n.d.). About Rapid. Retrieved December 21, 2022, from https://rapid.exlibrisgroup.com/Public/About

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (2021, June). IFLA position on controlled digital lending. https://repository.ifla.org/bitstream/123456789/1835/1/ifla_position_-_en-_controlled_digital_lending.pdf

Lomba, C., Marzocchi, S., & Mazza, D. (2023). HERMES, an international project on free digital resource sharing. In F. Renaville & F. Prosmans (Eds.), Beyond the Library Collections: Proceedings of the 2022 Erasmus Staff Training Week at ULiège Library. ULiège Library. https://doi.org/10.25518/978-2-87019-313-6

OCCAM’S READER. (2021). About. Retrieved December 21, 2022, from https://occamsreader.lib.ttu.edu/about/index.php

OCLC SHARES. (n.d.). International ILL toolkit. Retrieved January 30, 2023, from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1bL94PplzLTXYyxWNRnwQj4cn6YhCo62V4kFHhW0S15E/edit#gid=0

Posner, B. (2019). Insights from library information and resource sharing for the future of academic library collections. Collection Management, 44 (2–4), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1593277

Rodriguez, M. (2021). Licensing and interlibrary lending of whole eBooks. Against the Grain, 34(4), 17–18. https://issuu.com/against-the-grain/docs/atg_v33-4/s/13538491

Roll, A., Lee, C., Fraenkel, J., & Murphy, W. (2022, February 23). The key to modern resource sharing: whole ebook lending and more [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TCbppWTh3wg&t=11s

Roncevic, M. (2020). Digital rights management and books. Library Technology Reports, 56(1). https://doi.org/10.5860/ltr.56n1

SPARC. (n.d.). Controlled digital lending. Retrieved December 21, 2022, from https://sparcopen.org/our-work/controlled-digital-lending/

Weston, W. (2015). Revisiting the Tao of resource sharing. The Serials Librarian, 69(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2015.1021988

Wu, M. M. (2019). Shared collection development, digitization, and owned digital collections. Collection Management, 44(2–4), 131–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1566107