The gentle art of giving and receiving: Resource sharing services in a museum library

Florian Preiß

Abstract

Deutsches Museum library is one of the largest collections of literature on the history of science and technology. It shares its resources to a broad audience by interlibrary loan and document delivery. The latter is carried out as part of the Subito library network. Also, to share its collection online, the museum library takes part in the platform Deutsches Museum Digital.

Keywords

Museum library; Deutsches Museum; History of science and technology; Resource sharing; Interlibrary loan; Document delivery

Article

The Deutsches Museum, one of the world’s most distinguished museums for science and technology houses a library that is the largest museum library in Germany and one of the world’s leading research libraries on the history of science and technology.

Oskar von Miller, an engineer and pioneer of early electrification, founded the Deutsches Museum in 1903 to promote interest in scientific and technological advances among a broad audience. The museum’s exhibition building, situated on an island in the river Isar (Fig. 1), opened its doors in 1925 and replaced a provisional exhibition in Maximilianstraße (Füßl, 2010). The object collection grew fast and over the following decades the museum became a prominent place for science and technology education – and one of the major tourist attractions in the Bavarian capital. Before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in Europe in 2020, the museum attracted well over one million visitors a year.

The Deutsches Museum perceives itself as a research museum and operates its own research institute focusing on the history of science and technology and maintains close ties with the relevant departments of the three large Munich universities: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU), Technische Universität (TUM) and Universität der Bundeswehr (UniBW).

The Deutsches Museum library and its collection

The library has been an integral part of the museum from the very beginning. It relocated multiple times to several different locations in Munich until the present building was inaugurated in 1932 (Hilz, 2017; Hilz, 2021). Since then, the library building has housed the reading rooms, the offices and media storage in the immediate vicinity of the exhibition building (Fig. 2).

The library collection comprises more than 950,000 volumes, including a spectacular rare book collection of more than 15,000 books published prior to 1800. An extensive stock of historical journals, grey literature, patent documents, telephone directories, railway timetables, address books and unique resources also account for the library’s importance as the place to be for anyone conducting research on the history of science and technology in Germany. This is one of the reasons why the library, in cooperation with Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library, BSB) has been approved a “Fachinformationsdienst” (specialized information service) by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) since 2016, which entitles to additional acquisition and personnel funds (Hilz, 2021; Winkler, 2020).

Library services

While this Fachinformationsdienst aims to assist state-of-the-art research in the field of history of science and technology, the 25 library staff members also serve the everyday needs of museum staff, both academic and non-academic. All 586 employees and 184 volunteers (end-of-year 2021) may benefit from the full range of the library’s services including free interlibrary loan orders and they are entitled to request staff member library passes to borrow books. The same favourable conditions apply to those visiting scholars who are granted a scholarship by the museum’s research institute. The reading room with about 130 seats is not only open to staff and scholars, but also to the general public (Fig. 3). However, these external patrons are limited to a basic service without the possibility of borrowing books or placing interlibrary loan orders.

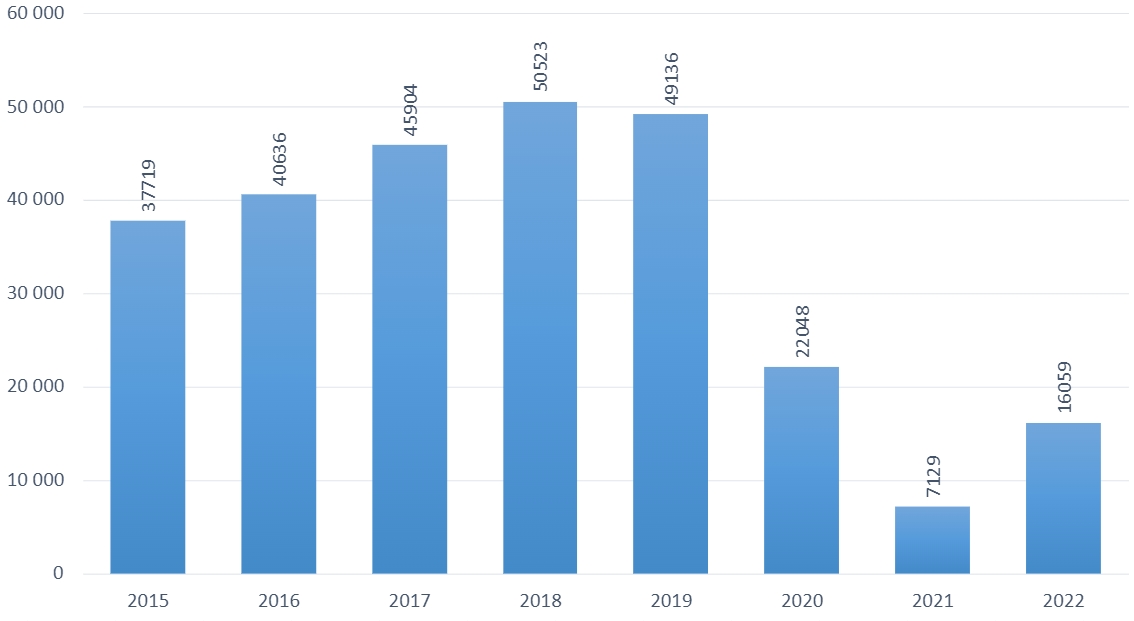

The number of external visitors reached the 50,000 mark in 2018 and just missed this peak in 2019 (Fig. 4). Due to the restrictions imposed by the authorities because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of visitors dropped sharply in 2020, reached a low in 2021 and have gradually started to recuperate in 2022. This dramatic decline in visitors had little impact on the statistics for inter-lending services: interlibrary loan and document delivery services remained in demand, and even increased in some parts. While many academic libraries in Germany had to shut their doors from mid-March 2020 for nearly two months and interrupted their inter-lending services, the Deutsches Museum library could continue operation despite the fact that some of the staff were required to work remotely (Hilz & Winkler, 2020).

Deutsche Museum library as a giving partner for sharing resources

The Deutsches Museum library is both a giving partner in the conventional interlibrary loan system as well as in the Subito network. In conventional ILL, it gives books on loan nationally and internationally and delivers paper copies to requesting libraries.

In 2019, the Deutsches Museum library became a full member of the library network Subito (Homann, 2019). This registered association is a non-profit organization of about 40 cooperating libraries, mostly from Germany with few members from Switzerland and Austria. These libraries started to cooperate in the mid-1990s to promote delivery of documents and to establish new (digital) methods of delivery. For a small fee, libraries worldwide as well as individuals and companies from Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Liechtenstein can open a user account and order via a simple webform. These orders come with a guarantee that they will be fulfilled within a maximum of 72 hours (24 hours for urgent orders, subject to a surcharge).

Digital deliveries for ILL and Subito however face various legal hurdles. Clasen (2019) recently published a comprehensive overview of legal issues and challenges in German interlibrary loan and document delivery. For example, the legal restrictions limit orders of copies from monographs to a maximum of only 10% of the content. And it gets most complicated when (paper or digital) copies from newspapers or newsstand magazines are needed: The strong position of publishers makes it virtually impossible to deliver these via ILL or Subito (unless the tangible originals are sent – but this is rarely the case, as huge bound volumes or fragile paper make it difficult).

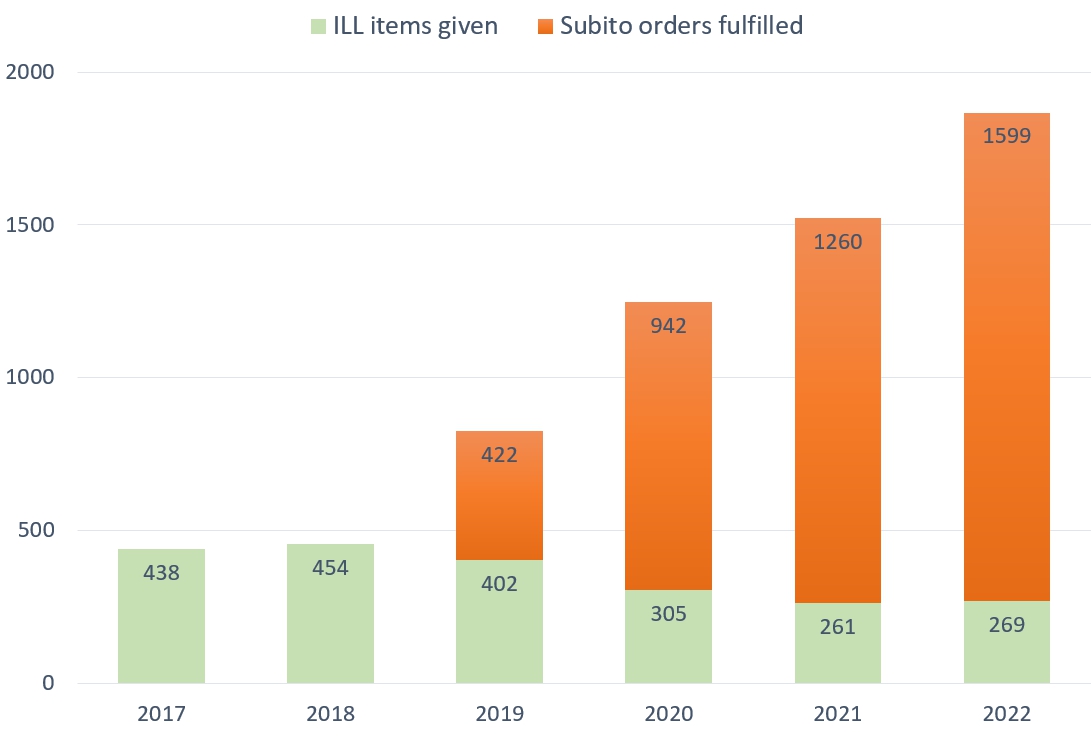

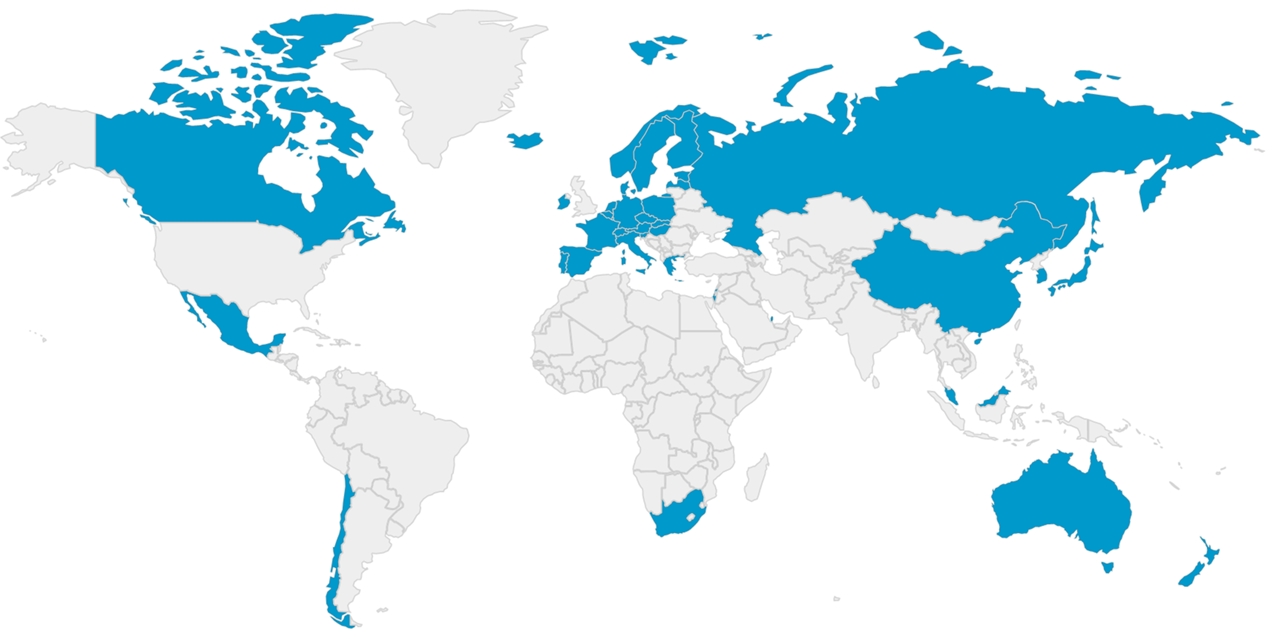

In recent years, the numbers of conventional ILL orders at Deutsches Museum library slowly descended from a peak of 454 delivered items in 2018 to a low of 261 in 2021. Subito orders on the other hand showed a huge growth in the first four years that the library has been participating: The amount more than tripled from 422 in 2019 to 1,599 in 2022 (Fig. 5). Although it looks as if this significant increase in orders resulted in an unreasonable additional workload, this is not the case. The workflow for processing Subito orders could be kept very lean and the easy delivery options via the Subito web application helped to minimize the workload. The centrally processed invoicing by the Berlin-based Subito head office ensures that the library staff is not burdened with this task in any way. In addition, the head office and the “Zeitschriftendatenbank” database (the German union catalogue for journals) as underlying metadata are responsible for checking deliverability from a legal point of view – so the library staff does not have to check whether incoming orders comply with rights management and licence contracts. All necessary licence fees that might potentially be requested by rights holders are cleared by the head office. In summary, the decision to participate in Subito meant, with minimal effort, increasing the visibility of the library’s collection and at the same time making it more available worldwide. This is clearly reflected in the origin of the orders received: While conventional international interlibrary loan orders regularly come in from barely a dozen countries, the Museum library has received Subito orders from six continents and 40 countries so far (Fig. 6).

Deutsches Museum Digital: sharing resources online

Deutsches Museum Digital[1] is the place where all the digitization efforts of the museum departments (archives, library and object collection) are brought together (Huguenin, 2019). In the future, this platform is thought to act as a one-stop shop to provide users with important research material from archival sources, library material and museum objects.

So, when considering the giving part of its resource sharing activities, it should not be forgotten, that the museum library’s digitization projects also play an essential role as they contribute to the online availability of relevant literature. To do this, the library is pursuing two strategies – “custom-made” vs. “mass business”, but in the end, the results from both processes will be hosted on Deutsches Museum Digital (Bunge, 2019). While the “custom-made” digitized books, on the one side, are created by the library staff themselves and focus on small, coherent collections of predominantly rare books, the “mass business”, on the other side, is an outsourcing cooperation in partnership with Google Books. Within the scope of this partnership, to date more than 50,000 non-copyrighted volumes (both journals and monographs, approx. 5% of the collection) have been digitized. Google Books is presenting these volumes on its own platform and hands over a library copy of the digitized material, which the museum successively provides on Deutsches Museum Digital.

The receiving part

For its internal users (i.e. staff and visiting scholars), the library procures virtually any book available worldwide that is needed. The importance of this procurement service is highlighted by the results of an anonymous survey conducted among library users in May 2022 (Heller et al., 2022): Among the 100 museum staff participants in the survey (among which 56 academic and 44 non-academic), only 16% always find all the literature they need in the museum library’s collection. This means that in most cases external library material is essential for professional and scientific work.

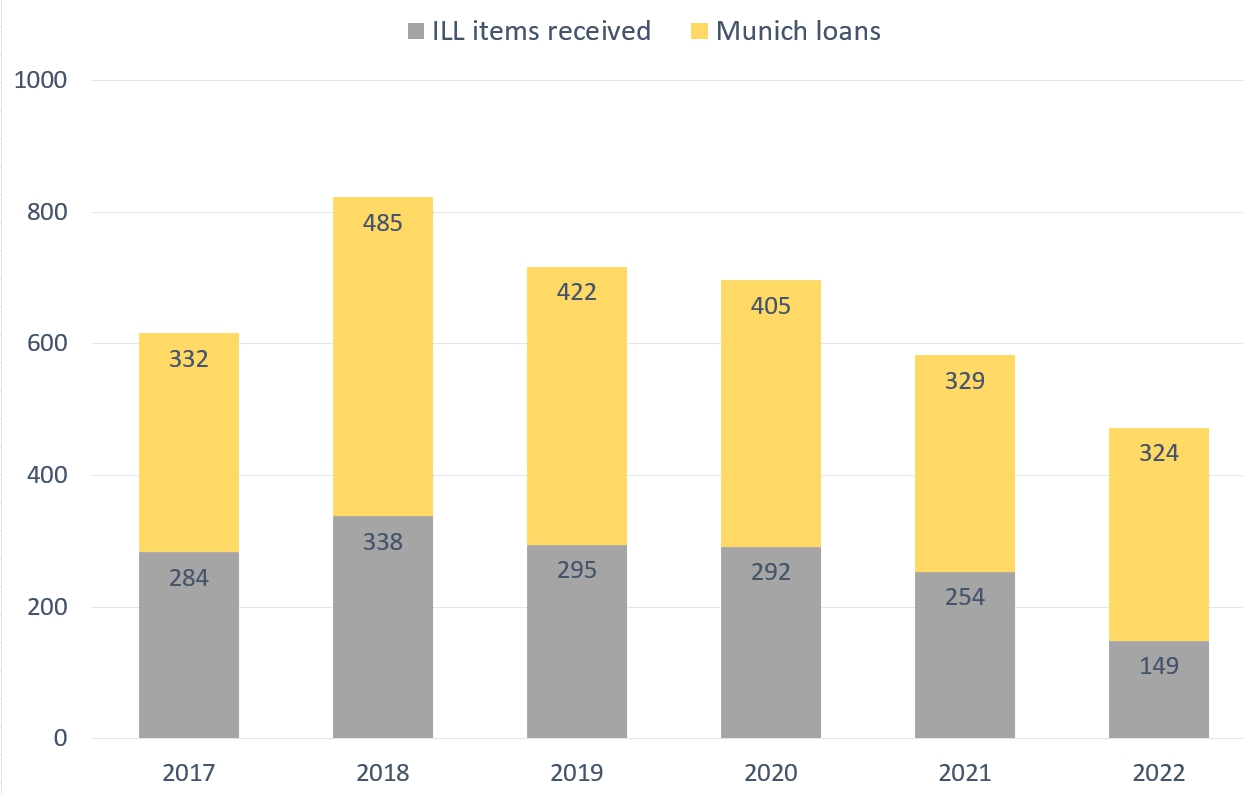

Most of the orders (regularly three fifths in the past years) can be fulfilled as a loan service from state library BSB and the two large university libraries LMU and TUM (Fig. 7). This service is called “Ortsleihe” (city loan). Therefore, a courier visits the respective libraries on a weekly basis and if needed more frequently to pick up the media that has been ordered by the museum’s ILL staff. The courier will then bring the media to the museum library and notify the users that their ordered documents are ready for collection at the circulation desk. The courier will copy or scan those media which are only for exclusive use on the premises of the respective libraries. As a result, thanks to the Ortsleihe service, users save themselves long walks or subway and tram trips through the city. They also do not have to worry about reminder fees, as the museum library’s accounts at BSB, LMU and TUM enjoy preferential conditions.

All documents that cannot be ordered within Munich will be ordered via ILL, first via the regional Bavarian Interlending network and, if necessary, Germany-wide. For ordering items from libraries in Bavaria and Germany, the library uses the ZFL tool (“Zentraler Fernleihserver” – a centralized ILL server application maintained by the German library networks). This tool can also be used for international orders, but the lending library in this case receives all the order details via a standardized e-mail.

Virtually all orders can be kept free of charge for the museum’s library patrons: Monographs in German interlibrary loans are shared on a reciprocal basis between libraries. Costs arise only for packing and shipping, but these are not charged to the user. The same applies to the occasional fees charged for copies/scans. However, as higher fees are often incurred in international interlibrary loans, it is not always guaranteed that these costs can be covered by the library. To pay for orders from foreign libraries, the Deutsches Museum library participates in the IFLA voucher scheme and also accepts payment vouchers from libraries abroad. In practice, a considerable surplus of incoming IFLA vouchers can keep all orders placed at foreign libraries free of charge for museum staff.

For urgent orders of papers needed by museum staff, the Deutsches Museum library may also act as an ordering party itself in Subito. In this case, it will be charged the regular fees by Subito. However, since one result of the anonymous survey (Heller et al., 2022) was that only about a quarter of internal users use these interlibrary and document delivery services, and almost a third are not even aware of it, there is still potential for increasing its visibility.

Allowing users to focus on their research

All these library services in their entirety form an essential part of the research infrastructure at the Deutsches Museum. They are highly appreciated by Deutsches Museum researchers, as they do not have to concern themselves with how and where to get literature and scientific information. They simply address their own institution’s library, which defines the supply of literature as one of its core tasks. On a national and international level, the Deutsches Museum library contributes to a wider network of resource sharing and inter-lending services, so that external users also may benefit from the Museum’s extensive historical sources.

Bibliography

Bunge, E. (2019, September 4-6). Boutique-Digitalisierung vs. Massengeschäft: ein Erfahrungsbericht aus der Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums [Conference session]. ASpB-Tagung 2019, Frankfurt a. M., Germany. https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-bib-info/files/16695/Bunge_Digitalisierung_DNB.pdf

Clasen, N. (2019). Digital possibilities in international interlibrary lending – with or despite German copyright law. In P. D. Collins, S. Krueger & S. Skenderija (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th IFLA ILDS conference: Beyond the paywall – Resource sharing in a disruptive ecosystem (pp. 92-100). National Library of Technology. http://www.nusl.cz/ntk/nusl-407836

Füßl, W. (2010). The Deutsches Museum and its history. In W. M. Heckl (Ed.), Technology in a changing world: The collections of the Deutsches Museum (pp. XIV–XVI). Deutsches Museum.

Heller, L., Morich, M., & Pietsch, A. (2022). Umfrage zur Nutzung der Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums. Unpublished survey conducted as part of a team course achievement at Hochschule für den öffentlichen Dienst, Fachbereich Archiv- und Bibliothekswesen München.

Hilz, H. (2017). Die Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums: Geschichte – Sammlung – Bücherschätze. Deutsches Museum.

Hilz, H. (2021). Bibliothek auf der Isarinsel: Geschichte und Gegenwart der Bibliothek des Deutschen Museums. AKMB-news, 27(1), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.11588/akmb.2021.1.89932

Hilz, H., & Winkler, C. (2020). Corona, subito und die Bibliothek. Kultur & Technik, 44(3), 50.

Homann, M. (2019). subito Document Delivery Zurück in die Zukunft in Zeiten des Wandels. b.i.t. online, 22(5), 422-425. https://www.b-i-t-online.de/heft/2019-05/nachrichtenbeitrag-homann.pdf

Huguenin, F. (2019). Deutsches Museum Digital: Online-Portal von Archiv, Bibliothek und Objektsammlung. AKMB-news, 25(2), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.11588/akmb.2019.2.72577

Winkler, C. (2020). Googeln Sie noch oder finden Sie schon? Kultur & Technik, 44(3), 48-53.